Search

DONATE

Protagonists

Main Themes

Location

Financial/Statistical Data

Featured Works

Key Events

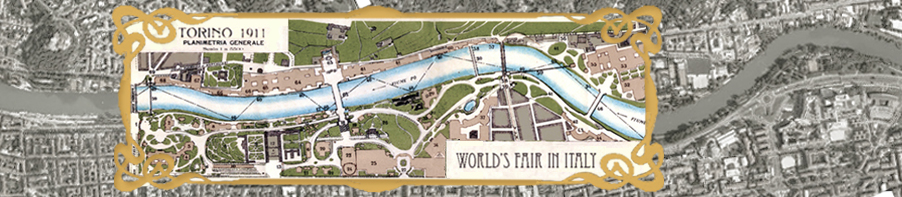

Turin:

The Nation’s Birthplace and A World’s Fair’s Home

The first issue of the 1911 World’s Fair’s official magazine, L’Esposizione di Torino 1911: Giornale Illustrato dell’Esposizione Internazionale delle Industrie e del lavoro (January 15, 1910) introduced the Fair in an article entitled 1861 and signed Tommaso Villa. Villa presented the Fair as the marvelous celebration of the upcoming fiftieth Anniversary of the Unification of Italy under the Savoy constitutional monarchy, and Turin, the former capital city and home to the royal family, as the most appropriate location to host the event. Magniloquent and apodictic in its statements, the article shaped the process of the unification of the country as a sweeping and decisive event--the inevitable outcome of the partnership between enlightened leadership and popular participation:

Nessun periodo della storia nostra offre un più mirabile esempio di fraterna concordia e un più grandioso spettacolo di generosi ardimenti e di intensa passione di quello che corre dalla pace di Villafranca al 18 marzo 1861, giorno nel quale avvenne la solenne consacrazione dell’unità nazionale. L’opera, giova ricordarlo, si compie in poco più di un anno.

In tones that are both messianic and populistic, Villa’s piece presents the creation of the Unitary state under the constitutional monarchy of King Victor Emmanuel as resulting from the unanimous and collective resolve of the Italian people and the beneficial intervention of God’s will. Villa frames Garibaldi’s expedition to Sicily (the famed Spedizione dei Mille) as representing the timely “risveglio della coscienza popolare” against the delays of diplomatic caution and political maneuvering. Garibaldi’s famed meeting at Teano with Victor Emanuel is similarly portrayed as expressing the General’s good-willed compliance with royal authority—the symbolic stretta di manowith which the man of the sword conceded leadership to the God-sanctioned, Turin-born father of the Italian nation.

Villa’s exhalts Turin—the seat of the royal House of Savoy—as the origin and the goal of the Unification’s sublime course—the center where the Italian family happily reunites: war heroes with political leaders and common people celebrating a motherland that is not a mere “aggregazione di provincie” but a living organism “dal Monviso all’Etna, dalle Alpi all’Adriatico”.

In writing his cliched rendition of the Unification process, Villa drew from widely popularized historical texts and popular narratives, the impact of which spred well into the twentieth century (see, for example, Blasetti’s film 1860). Only in the 1950s did revisionist historiographers such as Denis Mack Smith start to effectively question this epic and heroic emplotment of the birth of the Italian nation.

Villa’s article cannot be merely dismissed as a piece of hackneyed rethoric and amateurish historicism. Its very limits display the ideological foundations of the World’s Fairs Project. Villa’s claim to historical accuracy includes italicized quotations of the King’s speech on the occasion of the Inauguration of the Legislature on February 18, 1891 and of Count Cavour’s. While the King’s words emphasize the country’s destiny of freedom and unity under the aeges of Divine Providence and the good will of the neighboring “sister nations” France, England, and Germany, those by Cavour displayed Italy’s need to strongly assert its national right against the aggressive designs and condescending attitudes of Europe’s imperial powers (in 1847, Metternich had dubbed Italy as a mere “geographical expression”). For Cavour, Italy’s neighboring powers are no longer sister nations here but, quite bluntly, the “nemici al di la delle Alpi” (enemies on the other side of the Alps).

In pairing Victor Emmanuel’s conciliatory words with Cavour’s belligerant ones, Villa does not simply display the king’s and the prime minister’s differing political functions – one diplomatic and symbolic, the other practical and pragmatic. He rather reflects the very ideology that, a century after these foundational speeches, nurtured the Italian World’s Fairs as well as all Universal Expositions held in the Age of Nation and Empires, an age that can be summarized, with D'Ormeville as the age of “peace armed to the teeth.”