Search

DONATE

Protagonists

Main Themes

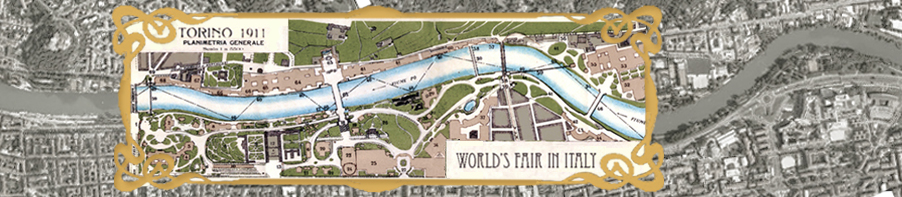

Location

Financial/Statistical Data

Featured Works

Key Events

The Touring Club Italiano in the Age of the World’s Fairs

An presence in Turin 1911, the Italian Touring Club was inaugurated in 1894 in Milan. Its original name was Touring Club Ciclistico Italiano (TCCI) and was formed by a group of 57 cyclists lead by Luigi Vittorio Bertarelli, an industrialist, writer, assiduous traveler, and sport enthusiast who served as the club’s main executive until his death in 1926. As the club’s logo demonstrates by featuring the Italian flag framed in a bicycle wheel, the bicycle (soon to be replaced by the automobile and plane) represented speed and technological progress, and was the catalyst of a sense of national pride, competition, and comradeship, as shown by the institution of the Giro d’Italia in 1909.

The Touring (as it came to be called after dropping the ciclistico in 1900,) was born under the sign of modernity and cosmopolitanism. Historian R. J. B. Bosworth observes that the Touring had a seminal role in spreading the gospel of modern technology, modern business practice, and modern leisure in Italy (347). The Touring’s first president, Anglo-Italian industrialist Federico Johnson, was a fitting representative of the club’s identity, one that simultaneously promoted a sense of national individuality and internationalism. Johnson’s double citizenship demonstrated the deep anglophilia that marked the club, and revealed a widespread feeling that modernity and progress were concepts that Italy urgently needed to import from abroad. Like the World’s Fairs, the Touring was indeed a phenomenon of emulation, as it replicated analogous initiatives in England and France. As such, it also displayed a sense of anxiety on the part of the Northern Italian bourgeoisie—the feeling that Italy had to catch up to the most advanced countries in Europe if it wanted to become competitive in the arena of nations and empires (Bosworth 375).

The Club's activities included promoting travel and tourism by advocating measures to systematize traffic, improve road signs, and expand means of transportation. The Club was active in supporting construction of new highways and upheld environmental awareness and preservation of the national historical and artistic patrimony. Always with an eye to more advanced foreign countries, the Club worked to enhance the quality of hotels and restaurants with the creation of training courses for hoteliers based on the example of Germany, Austria, France, and Switzerland. The Exposition of Turin 1911 was the perfect stage to further this mission, as demonstrated by the exhibit devoted to the Albergo Modello del Touring Club Italiano. The Touring was also a prolific publisher of maps and guides, and had enormous impact on the classification and reckoning of the country and (later) of its imperial possessions (Ottaviano 188-91). The first TCI guide to Eritrea was published in 1908 and the attack on Turkish Libya in 1911 was followed by the hasty publication of numerous maps and guides of the region. Journals such as the Rivista mensile del Touring also helped chart “what there was to be seen in the Italian world and how it was best, most efficiently, most expeditiously, most instructively, and thus most patriotically, visited

While the Touring always defended its political neutrality, it had a fundamental impact in "charting the course of at least the Italian bourgeoisie to a certain sort of modernity and to a variety of national identity"(Bosworth 373). Bosworth argues that "It might almost be alleged that, to be a middle-class Italian, you had to belong to the TCI" (374). By 1911, the Touring counted 100,000 subscribers (Bosworth 373) and before World War I the Touring's publications reached one Italian family in ten (Rosselli). If, just after the Italian unification, Massimo D'Azeglio had famously stated “L'Italia è fatta, ora bisogna fare gli Italiani," (Italy has been made, now we have to make Italians), in 1901 Bertarelli curtly replied: "Italy will make Italians." Bertarelli thus evoked a stronger connection between the nation-state and its inhabitants, that is, between the notion of a shared, known, and classified national space and the people who derived their identity from it. The Touring took upon itself the didactic task of "far conoscere l'Italia agli Italiani"(L'Italia e il Touring Club 3, 6).

However, in spite of the touted goal of building a sense of collective national identity, the process of making (middle-class) Italians was initiated and controlled by the Northern Italian bourgeoisie and therefore hardly a mirror of the country as a whole. In 1907, for example, the Club counted only 82 members in Catania and 22 in Caltanissetta compared to the 9687 members of Milan and the 4879 of Turin. Like the World's Fairs, the CTI worked by exclusion as much as by inclusion, and if in January 1911 the Club declared itself to be be un "istituto eminentemente nazionale" (Rivista mensile XVI), all its executives and leaders came from, worked, and lived in the Piedmont-Lombardy area.

Cover Page, Touring Club magazine, August 1910Bibliography:

R. J. B. Bosworth. "The Touring Club Italiano and the Nationalization of the Italian Bourgeoisie." European History Quarterly 27.3 (July 1997): 371-410

Ottaviano, Chiara. "Classi agiate e organizzazione del tempo libero." Valerio Castronovo. La cassetta degli strumenti: ideologie e modelli sociali nell'industrialismo italiano Milan: Franco Angeli, 1986. 169-94.

G. Rosselli. "Turismo e colonie: Il Touring Club Italiano." Giuliano Gresleri. Architettura italiana d'oltremare 1870-1949. Venice: Marsilio, 1993.

G. Rosselli. "Turismo e colonie: Il Touring Club Italiano." Giuliano Gresleri. Architettura italiana d'oltremare 1870-1949. Venice: Marsilio, 1993.

L'Italia e il Touring Club negli scritti di Luigi Vittorio Bertarelli. Milan: TCI, 1927.