Search

DONATE

Protagonists

Main Themes

Location

Financial/Statistical Data

Featured Works

Key Events

The Valentino Park: the ideal location- by E. Raspi

Oggi una fitta selva di antenne: l’ossatura enorme, che si profila sulle delicate armonie de’ grigi della collina, assorta nel letargo invernale; la pianta nuda, severa e triste delle forme ischeletrite. Domani una gloria di orifiamme sventolanti lietamente al sole; l’ossatura rivestita di muscoli rigorosi, per entro i quali fluisce la vita di venti nazioni; la gioia spensierata delle frondi e dei canti.

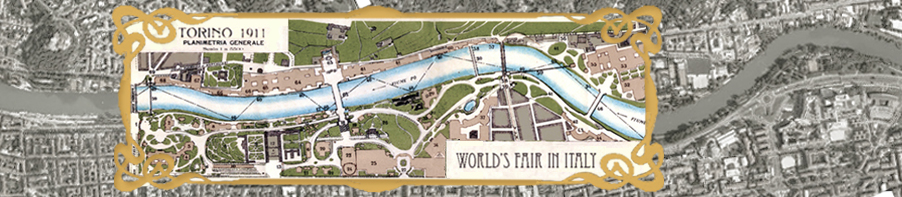

As mentioned the citation above, taken from the first issue of the Giornale Ufficiale Illustrato dell’Esposizione Internazionale delle Industrie e del Lavoro (1910), the International Fair of 1911 appeared as “a dense forest of antennas” due of the effect of its more than one hundred pavilions and structures, along the Po river banks. The Fair reflected the esthetic inclinations of Modernist Literature, and the relentless spirit of the beginning of the Twentieth Century: a symbiosis of Nature and Steel, where the floral and delicate motifs of Art Nouveau met the strength of metal and technical advancements.

A detailed yet poetic depiction of the entire complex of the Fair is suggested by the Giornale ufficiale, specifically in the first issue of 1910, entirely dedicated to the history, description and aggrandizement of the urban park. The article describes it as the true heart of Turin, and reason of pride for all the citizens; the author is even emotionally touched in explaining the ancient origin of the Park's name, beside its recent creation (XIX century), and its central role in the Turinese Fair's season. Although it has been chosen as ideal location for the fairs of 1884, 1889 and 1902, the 1911 exhibition expresses a desire for celebration (in fact, it is the fifties anniversary of the Reign of Italy), and the signs of an always-increasing intervention of Man over Nature, thanks to the discovery – and display- of enormous technological advancements.

In fact, during this occasion, the committees decided once again to take advantage of the complexity, and variety, of the natural surroundings: they reorganized gardens and boulevards , and they transformed the Po river from physical border to main attraction. For instance, we can only imagine the effect that the night view of Monumental Bridge and Fountain had on the viewer, thanks to the intricate and unique reflections of both natural and artificial lights on the water surface. The Bridge was specifically built for this Fair, as many other temporary installations, and it harmonically echoed the general style of the Fair in its majestic details. In addition, the Bridge functioned as ideal link between the two side of the river, therefore enclosing the natural barrier of the water within the scope of the Exhibition itself. The Po was not only a way to access the Exhibition, but it became the center and a constant presence between every event.

The Valentino Park has been built between 1850-1870: the second half of the XIX century was a crucial moment in Turin's history, as the city was working to become one of the most influential industrial - and cultural - cities of Europe, and to once again establish its traditional position as cultural role model in the Old Continent. Consequently, the decision to change the status of the Park from private to public was part of the process of development and rethinking of the entire city. Furthermore, the Park did not just meet aesthetic requisites, but it responded to urgent demographic and politic needs, as it served as a symbol of the emerging, powerful bourgeoisie , and of the Royal Family of Savoia, at the time ruling over Italy. To better understand these urban and aesthetic decisions about the Park, as we mentioned before, they need to be compared to other similar international choices and changes, such as the Regent’s Park and the Victoria Park in London, and the Bois de Boulogne in Paris. In fact, moved by practical reasons and positivist ideals, governments decided - as priority - to create places where citizens could spend their spare time and enjoy the natural environment. In this sense, we could refer to the park as hortus conclusus, in other words an enjoyable, closed and protected space, where the human manipulation is (at least on the surface) close to zero. The construction of such spaces, though, is artificial itself and represents the celebration of the human mind and social structure: the Park is not a virgin and wild portion of nature, but it is accurately designed in order to meet the intellectual expectations of its creator, and to channel the need of free space of the modern Man.

Before long, the green space becomes both a chance of leisure and escape from reality for the lower social classes, and a mirror of the bon ton and life of the middle class: the park, thanks to its elegant forms and aperture, is the ideal place for long walks, open air games, and dejeuners sur l'herbe (and above all a crucible of social interaction, a display in which people seeked to be noticed). Therefore these spaces, representing everything outside of the day-by-day reality, allow people to experience doses of freedom, participate in social events and, potentially, escape from other people's gaze. Consequently, the park becomes a liminal space, in its being both mirror for social rules and locus of transgression of those same rules.

Ultimately, the social and aesthetic connections between the eccentric and transgressive personality of the International Exhibitions and the space of the park, should not be surprising. They do not just answer practical and simple needs, but follow a more subtle, precisely planned direction: the Exhibitions, in fact, seems able to declare and exaggerate some of the peculiarities already present in the park (in their embryonic stage), such as the display of social power and status, exhibitionism, celebration of beauty, transgression, and scandal.