Search

DONATE

Protagonists

Main Themes

Location

Financial/Statistical Data

Featured Works

Key Events

Torino Esposizione 1911

Monografia illustrata edita dalla Direzione Generale del Touring Club Italiano col concorso della Commissione Esecutiva dell’Esposizione di Torino 1911

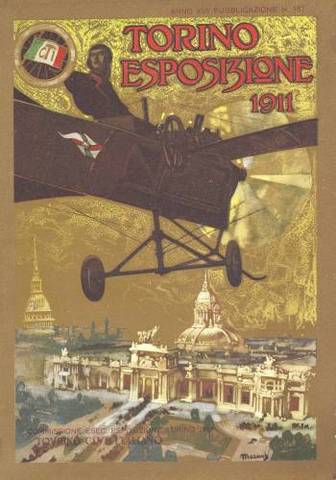

Torino Esposizione 1911, published by the Touring Club Italiano (CTI and, later, TCI) was one of the most popular tour guides to the 1911 Exposition. The guide’s cover page features a color illustration presenting an aerial view of the Fair. In the background, on the left side, one can see one of Turin’s most famous urban landmarks: the dome of the Mole Antonelliana. Dominating the composition, in the foreground, is the icon of modernity and progress: a propeller plane flying over the city. Mario Stroppa, cover illustration for Torino Esposizione 1911

Just like the plane’s pilot, the guide’s users occupy the privileged and dominating position of someone who can cast a panoramic glance over the entire city and its marvelous fair. If a guide’s conventional function was to inform and direct visitors who were presumed to be unacquainted with their surroundings (its aim being, therefore, both practical and didactic), the CTI cover page immediately gave its readers a sense of power and “panoptic” control over the city and the fairgrounds stretching, on display, below them.

The designer of the CTI guide’s cover page was Mario Stroppa, aka Marius (1880-1864), a gifted graphic designer and inventor who trained in Milan (he attended the Scuola Superiore d’arte applicata alle industrie in the Castello Sforzesco and enrolled in the Academy of Brera, without completing his degree). As architectural illustrator, Stroppa collaborated with numerous magazines and newspapers, including Il corriere della sera and Il resto del Carlino. “A master of perspective,” writes Esther Da Costa Meyer, “Marius specialized in architectural renderings of bird’s-eye view” (131). He created many cover illustrations for the monthly publication of the Touring Club Italiano. His fame among his contemporaries was especially tied to his work for numerous expositions: besides designing the lithograph poster for the 1905 exposition in Milan, he decorated the Italian Pavilion at the Exposition of Brussels in 1910-12 with thirteen panels representing Italy’s most famed cities. Unfortunately, a fire destroyed this display. A visionary, if eccentric, inventor, Marius was a typical representative of the exposition age and his machines displayed modernity’s faith in technology and the power of the human mind to conquer space and time.

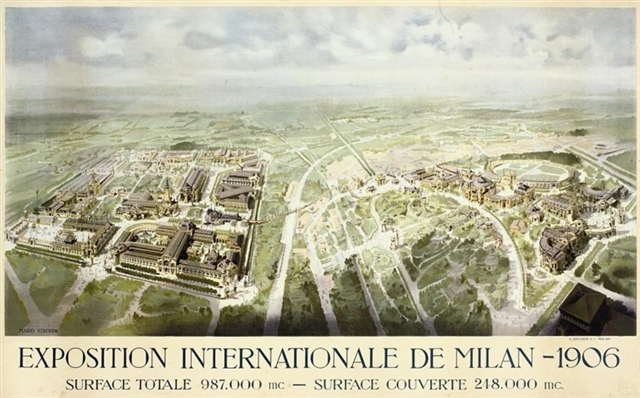

Mario Stroppa, Color lithograph poster of the 1906 Exposition in Milan.

Turin, Italy’s Industrial Capital

Torino Esposizione 1911 is divided into two sections and addressed to Italian-speaking non-Turinese tourists. The first section furnishes a brief history of the city of Turin, starting from its origins and lingering on the Risorgimento, which is presented as promoted and shaped by the “Mecca” of Turin, the “silenziosa preparatrice del riscatto nazionale” (silent promoter of national redemption) (7). The CTI guide’s history of Turin mirrors the linear and evolutionary pattern of all Expositions’ master narratives. The past logically leads to a present of formidable achievements, which, in turn, announces an even more promising future. According to the CTI narrative, after leading the process of Italian unification, Turin blossomed into the nation’s main “centro di attività industriale e commerciale” (center of industrial and commercial activity). A paragon of efficiency, rational order, and prosperity in all its institutions, Turin is the epitome of a “città moderna” (modern city) (8). “Chi pensi [. . .] a quali criteri razionali s’informi [. . .] la vita sociale dell’oggi,” writes the anonymous author of the CTI guide, “non può non dire che il passo fatto verso un maggiore e complesso benessere materiale e morale sia stato enorme” (if one thinks about [. . .] the rational criteria that inform today’s social life, one must admit that we have taken enormous steps toward a bigger and more complex material and moral well-being) (22).. Rome (the nation’s capital city) and Milan (Turin’s archrival in business and industry) are mentioned hardly at all here, as Turin’s proudly sets itself in competition with the metropolises on the other side of the Alps, rather than with other Italian cities.

The CTI guide offers two city itineraries for visitors in Turin: a two-day and a five-day itinerary. It is meaningful that while the guide lists numerous historical palaces, piazzas, museums, and urban sites, the city’s many churches are barely mentioned. The five-day itinerary briefly notes the Cathedrals of Superga and San Giovanni, the Chapel of the Sacra Sindone, and the Church of the Consolata with its “ingenui segni della fede popolare” (naive tokens of popular faith) (13)—a clear sign of the anticlerical, scientific, and liberal bent of post-unification Turin, and a clear act of differentiation from papal Rome.

Surface Tours and Deep Currents: The CTI Guide Exposition Itineraries

The second part of the CTI guide is devoted to the Exposition and opens with a statement of collaboration between Italy’s two capital cities. The historical capital (Turin) and the present capital (Rome) are seen as joining hands in celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the nation’s unification: “Roma e Torino si affratellarono in un grande intento: quello di dimostrare alle nuove generazioni italiane, ed al mondo intiero quale grande cammino il nostro paese abbia percorso dal giorno in cui il Parlamento Subalpino lo proclamò ricomposto ad unità di Nazione” (Rome and Turin came together in a grand plan: that of demonstrating to the new Italian generations, and the entire world, what great itinerary our country has followed from the day in which the Subalpine Parliament proclaimed it as reunited in one nation). However, this progressive itinerary reverses the paradigms of the “old” and the “new.” Rather than presenting itself as the famed historic (and superseded) capital city, Turin displays itself as the modern host of the industrial World’s Fair—a fair that celebrates all the “manifestazioni dell’attività economica” (manifestations of economic activity) of a world in rapid evolution. As far as the CTI guide is concerned, Rome must rest satisfied with hosting the artistic and historic exhibitions, that is, with celebrating the past that heralds the modernity that Turin claims only for itself. Rome, in other words, stands for the country’s illustrious past. Turin is its industrial present.

Although not stated explicitly, the CTI guide was written with two main underlying goals: nationalistic affirmation and cosmopolitan emulation. Specifically, Turin 1911 aimed at:

- 1) Underscoring the modernity of Turin by emphasizing its technological and industrial achievements and by maintaining an ongoing comparison with the achievements of industrial nation-states of France, England, and Germany, with an emphasis on France. It is noteworthy, for example, that the first pavilion to be mentioned in the section devoted to the Exposition’s buildings is the Machinery Hall (19). The host of the CTI’s guide grand finale (as the last Pavilion to be described at the end of the six-day itinerary) is the Pavilion of France.

- 2) Underscoring the originality and nation-and-city-specific uniqueness of the Turinese fair. For example, the guide gives special attention to the style of the Pavilions, which reproduce the Turinese baroque rather than mimic a more generic “exposition style” (comparing Turin 1911 with Chicago’s White City, for example, just because some of the buildings featured white plaster, is both superficial and uninformed). The Guide also pays special attention to Pavilions unique to the Turinese fair, such as the Palazzo del Giornale.

The CTI guide provides a one-day and a six-day itinerary to visit the Exposition. The one-day itinerary was inspired by the synoptic logic of the World’s Fairs and its aim was to offer a rapid overview—a panoramic synthesis—of the exhibition according to the rushed and synergetic tempo of modernity. Here the hermeneutical logic is that of the gaze (“vedere” rather than “visitare,” says the author)—a gaze that allows the quick accumulation of all the “impressions,” “sensations,” and “images” that energize and excite the modern tourist. Overall, the visitor is put in a position of experiencing a barrage of “emotions”—of feeling the sensory overload that was the mark of urban modernity—rather than acquire methodical knowledge.

The six-day itinerary did not provide substantial differences from the one-day itinerary. The route to follow and the stops to make remained the same, and the only difference was the amount of time that visitors were expected to spend in each zone and each pavilion. With a more leisurely pace, the six-day itinerary, favored reflection—and the reader was invited to contemplate and recognize “the organic criteria” and “learned methods” with which the exposition was organized: “La grande Mostra [riflette] il concetto logico ed organico col quale procede e si svolge la legge economica del lavoro e della produzione” (the great Exposition [reflects] the logical and organic concept that governs and unfolds the economic law of labor and production) (18).

Whether the emphasis was on immediate “awe” or systematic “reflection,” the deep and unrecognized motivators of the Fair, competitive emulation and the anxiety of self-definition, remained concealed by a spectacle inspiring passive wonder or buried under the heavy lid of logic and scientific method.

Bibliography:

Esther Da Costa Meyer. The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia. Retreat into the Future. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995.